[Draft] The (Illusion of) Self and the 2025 Nobel Prize for Medicine

How, at the molecular scale, does a living organism distinguish itself from foreign molecules or invading pathogens? When that discrimination fails, we see autoimmune disease.

Fractals, Ancient Wisdom, and Immune System

From the fractal tendrils of a fern to the vast spirals of galaxies, nature delights in echo, repetition, and patterns at different scales. It was a paper by Prof. Elizabeth Bradley that first alerted me to the significance of both Mandelbrot’s fractals and the Vedic idea of “Yathā piṇḍe tathā brahmāṇḍe!” from Indian scriptures. Prof. Bradley emphasized the power of analogical thinking by drawing comparisons between the human immune system and the safety and security institutions of a nation in her paper on global grand strategy. While reading it, I distinctly remember reflecting on how our immune system recognizes what is us versus not us—a critical form of discriminatory knowledge that keeps the human body healthy.

In Bradley’s paper, she invoked analogy — comparing the immune system’s regulatory networks to policing, surveillance, and diplomatic institutions — to illustrate how a society and a body both require mechanisms of discrimination, protection, and reciprocity. I distinctly remember the moment: as I read it, I thought, “If our cells can discriminate self from non-self, then the self is not merely an abstract mental construction — there is a material substratum to it.” The idea flickered: self is not illusion; it is embodied, woven into biochemical pathways.

This reflection haunted me. How, at the molecular scale, does a living organism distinguish itself from foreign molecules or invading pathogens? When that discrimination fails, we see autoimmune disease: the body attacking its own tissues. I had read that the global burden of autoimmune conditions—if one includes indirect costs like lost productivity and caregiver burden—might run into the half-trillion-dollar realm. But more than the cost in money, it is the cost in suffering, in broken lives, in trust betrayed by one’s own flesh.

Then, this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine arrived, as though the cosmos had responded to that inward longing. The Nobel Committee awarded the prize to Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi for their discoveries about regulatory T cells and “peripheral immune tolerance” — how the immune system restrains itself from attacking its own body.

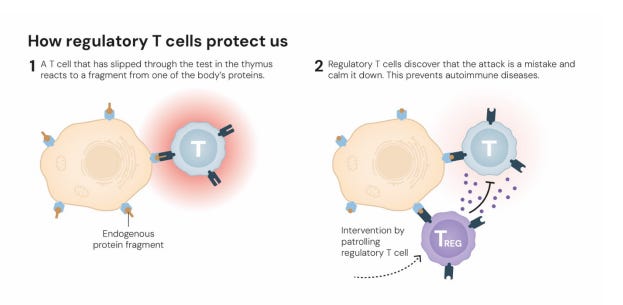

In terse, elegant language: our bodies are not simply war machines forever attacking invaders. Instead, they have guardians — regulatory T cells (often called T regs) — cells whose job is to suppress or brake immune activity when needed, so that healthy cells are spared. Sakaguchi first identified this subclass of T cells. Brunkow and Ramsdell then discovered that mutations in the gene FOXP3 derail regulatory T cells, leading to severe autoimmune pathology in mice and a human syndrome (IPEX). Their work showed how essential those “peacekeeper” cells are, how they prevent friendly fire in the body.

It was as if a light switched on. Here was a molecular mechanism intimately tied to the question: why we are not at war with ourselves. The self is not simply a philosophical or psychological idea — it is enforced, moment by moment, by cells that say “stay calm,” “stand down,” “do not attack.” The immune system’s internal architecture mirrors the most profound idea of selfhood: an organism must protect its core, yet allow relations, yet hold internal restraint.

Standing in awe, we can perceive something profound: the immune system is not just defense, it is discernment. It maintains the boundary of identity. And now, in the light of the Nobel discovery, the boundary of self is seen as coextensive with this regulatory architecture.

We might imagine a simplified metaphor: in a city, police and courts prevent the citizenry from violence among themselves; in the body, regulatory T cells prevent immune overreach. When the policing fails, riot becomes autoimmune disease. When regulation is robust, peace prevails. Bradley’s analogy becomes more than metaphor — it becomes biochemistry.

Through this lens, the phrase “Yathā piṇḍe tathā brahmāṇḍe” resonates with fresh urgency: the patterns of order, control, and discrimination recur from cell to society to cosmos. The fractal insight of Mandelbrot — that complex patterns repeat across scale — finds biological counterpart: whether population or lymphocyte, the same logic of selfhood and regulation recurs.

And this is not idle wonder: the Nobel laureates’ discoveries are already bearing fruit. Clinical trials are underway exploring therapies that boost regulatory T cells to treat autoimmune disease, improve transplant outcomes, or tune cancer immunotherapy. The very molecules that ensure selfhood may be harnessed to heal when selfhood falters.

Thus, the “cost” of autoimmunity is not simply monetary. It is metaphysical: a failure of coherence, a betrayal of self by self. But in the new light of molecular discovery, we glimpse redemption: the self is held in being by networks of cells that whisper “this is me” in every pulse, in every breath, in every antigenic encounter. The self is no longer vanishing mist — it is stabilized, dynamic yet anchored, by threads of regulation.

In the silent elegance of regulatory T cell circuits, we catch a glimpse of cosmic symmetry: the body’s microcosm echoes the macrocosm’s order. Self and universe, cell and cosmos, dance in fractal resonance. The Nobel Prize is not just a reward in medicine — it is a hymn to wonder, a testament that the boundary between self and world is biological, tangible, awe-inspiring.

As I close my reflections, I feel gratitude: gratitude to Bradley’s seed of analogy, gratitude to the molecular biologists who peer into the infinitesimal, and gratitude to life itself, which sustains the mystery of self — not only in mind, but in the living tissue of T cells, regulation, and cellular knowing.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Disclaimer: AI tools were used in curating this content, with human oversight to ensure rigor and contextual relevance.